In recent years, repeated news of femicide have reached our ears – almost every other day. The need to re- evaluate our interaction with them has prompted us to write this text and we believe it is a discussion worth opening up to the rest of the movement.

Nowadays, the news of femicide in Greece is being reported, and in a period when things are going terribly, we find ourselves unable to react. We are numb and apathetic in the face of violent and horrific crimes, of which we learn every horrifying detail whenever we briefly open our mobile phones. And when we muster the courage to write a text or call for a march, we are faced with total defeat. Our marches are not crowded, our texts have nothing new to say, and above all we seem to carry the sole responsibility of responding to gender violence-after all, we are the feminist collective of the city.

And that’s where we see a very basic problem. Gender violence, even in its most violent manifestation, seems to be treated separately from the other issues that the movement is dealing with. There is a contradiction in the way it responds to other kinds of systemic killings (of refugees; migrants; prisoners) versus femicide. It seems that these are not evaluated as a result of systemic oppressions.

We wonder if in the end, the system’s assimilation of the feminist movement has at last achieved its purpose – to prevent it from being recognized by the majority as something radical. No matter how much we talk about intersectionality, gender issues still fail to be included by the movement in its other struggles.

The way in which the mainstream media reproduce femicide and gender violence -in their own assimilated and depoliticized way- intensifies even more the prevailing perception.

So what the fuck do we do? As people who are politically active in a provincial city in Greece – Ioannina – we notice that the prevailing practices of calling for marches and courts are not enough. We wonder if this is just a problem in the micro-scale of our city and the ways in which there could be collective responses to such oppressions.

The femicides of Eleni, Caroline and Susan

On the 28th of November 2018, Eleni Topaloudi was murdered. Eleni was a 21-year-old student in Rhodes, and became a “martyr” figure for gender violence in Greece, in a society desperately seeking enlightened messiahs and martyr saints.

This crime was not just another case that played on the news for a few days or weeks, only for it to be forgotten when the next one comes. The brutality of the crime and the gruesome details broadcast by the media, gave the femicide all the characteristics needed for it to reach a nationwide scale, causing widespread socio-political reactions by anti-patriarchal collectives and even the prosecutor who took part in the trial of the case.

Her murderers are Manolis Koukouras and Alexandros Loutsai, whose crime was not reproduced by the mainstream media as a “murder”, but as a “femicide” and thus, the term was introduced into Greek society.

Eleni had the ideal profile for the media: white, Greek, modest, inexperienced; characteristics disproportionate to the brutality of her murder – she is the “perfect victim”. Eleni was raped, beaten, tortured and drowned. At the same time, the media did not hesitate to focus particularly on one of the perpetrators, a foreigner with a criminal record, a profile that satisfied the racist narrative of sovereignty.

The case of Eleni Topaloudi was the first case where the term femicide was widely used, not only by antireport media, but also by the mainstream media.

A few years later, in 2021, another femicide occurred, crucial for the establishment of the term in Greece, that of Caroline. This case monopolized television time, both in the news reports and in the morning panels, which presented it by including all the tragic details of the crime, as always with zero respect for the victim. The news reports in those days seemed more like episodes of an American crime show with graphic depictions of the crime and tearful statements by her “tragic” husband and widower father. The peak of the case was a “dramatic plot twist”, the confession of the woman-killer Babis Anagnostopoulos. In the 37 days leading up to this, the media accused a hypothetical gang of foreigners that spread fear in the region, revealing once again the states and capitals foundation: racism and fascism.

Caroline’s femicide destroyed the previously common profile of the woman-killer, the passion-blinded husband/ relative, often characterized as part of the working class with a lack of education. This time, the woman-killer was first and foremost Greek, educated, wealthy, a pilot by profession, the ‘ideal’ man according to the “excellence” standards of neoliberalism. Therefore, the narrative that wanted woman-killers to be a special case, collapsed.

From Caroline’s femicide up to the first femicide in 2022, 22 recorded femicides took place in Greece. And on the 20th of February 2022, 79-year-old Susan is murdered by her 69-year-old husband Spiros Nutsos in Ioannina.

The local media share the news: foreign-American woman ends up dead after getting beaten up by her husband, who initially states that she “fell and hit herself”. The neighborhood seems to have known how Spiros was abusing his wife, or more “decently” “he was a mean and difficult man,” and yet remained silent.

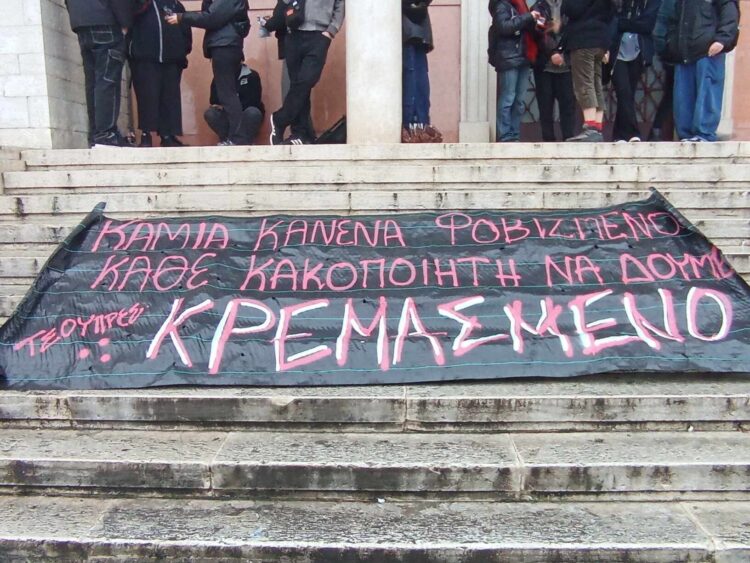

The next day, a reflexive march was called, flanked by anarchist, anti-authoritarian and leftist collectives, that ended up outside the apartment where they were staying. The march, although dynamic, was supported by certain individuals, the constant and active members of the movement. In a provincial town such as ours, we all know each other. The maximum upgrade, like pretty much in every march in Ioannina, was the stencil paintings on the neighbourhood, which shockingly are still there.

Susan’s femicide did not leave a mark, neither in the (local) movement, nor in the (local) community, since it wasn’t as shocking and cinematic as other widespread cases.

We never found out the trial date of the case, nor what happened there, and probably because we were not interested enough to do so, a pattern the movement follows when it comes to gender violence cases.

Of course, it is not that simple to talk about gender violence in Ioannina and our political activity concerning it, since the cases that make it to us are only a few. Because of the small scale of the society, these are often not made public by the survivors’ choice. Instead, they reach us in the form of “political gossip”. In the cases where our political intervention has been requested, we have acted either as collectives or as initiatives, in consultation with the survivors and to the extent that we are allowed to do so. There are however political groups that choose to act without the consent of the survivors.

Lately, there has been a very advanced and heavy case of gender-based violence going on in the Ioannina courthouse, which has been supported by an unusually large number of people, even outside the movement. This is because, in addition to the movement’s contribution, the survivor has chosen to publicize the case to the mainstream media, which in turn, has reproduced the case in their usual way.

Femicide representation on systemic media

It is remarkable how femicides and gender violence in general, are used by the media to gain exposure, choosing which cases to propagate depending on which are the most appealing to the viewer.

The term femicide, once established in the mainstream media, has turned from being an aspect of patriarchal violence – accompanied by interconnected oppressions – to functioning merely as a focus of legal controversy and as a tool to manipulate emotions (those of the viewers/consumers).

The controversy over whether the term “femicide” is valid or accurate, is an indication of an attempt to distract the viewer from the actual issue. After the first widespread femicides in Greece, morning shows and panels debated about whether the term femicide should be used, instead of homicide. The contrast between the wide coverage of the issue and the levity shown, is infuriating. In panels on such topics, the speech is usually given to various uninformed masculinities or femininities in positions of power, with questions such as “what was she wearing?”.

A transgressive example is Balaskas, a “union cop” (lol) that was invited to speak on one of the panels, on the subject of Caroline’s femicide, and basically explained what Babis Anagnostopoulos should have done to avoid a life sentence. He thus gave reached out to potential woman-killers, advising them to turn themselves in, immediately after the crime in order to escape a life sentence, thus creating the dominant pattern that is repeated to this day.

At the same time, the news broadcasts presented the femicides in such a way, as to distance the viewer from the incident and create the impression that they occur outside the micro-society in which they live.

This condition was reinforced by the social isolation due to the quarantine in the midst of the pandemic. At that time, the public was daily bombarded with bad news, including countless reports of gender violence, that during the quarantine period, increased. The poor state management of the pandemic and what came out of it, managed to politicize and radicalize a portion of the Greek society -or rather give the temporary illusion that it did. Thus, a temporary, and most importantly online, ‘community’ of people was built that recognized gender violence and femicides and spoke (or rather posted) about it.

This conversation was set within the narrow framework defined by the media, where information is tailored to be consumed, to raise the shock and fear of the news enough so that we return for the next article or reportage.

Consequently, every time we see the horrible result of misogyny and systemically entrenched sexism played out like a badly written Hollywood movie. Whether it is about perpetrators blinded by passion and victims who were in the wrong place at the wrong time, or about killers who are evil by nature, because they are mentally ill, foreigners or poor – all the people the system needs to demonize in order to perpetuate its existence at their expense. The victims are portrayed as unfortunate and martyred who did not deserve what happened to them because they were mothers and good wives or virgin Christians. And it is these cases of femicide that the mainstream media will showcase.

It is no coincidence, after all, how the term femicide, as used by the sovereignty, does not refer to all of us. We could never all be included in a term like femicide in the way it is replicated in the media, because they analyze etymologically the first compound of the term.

The only woman worth addressing is the one who carries the innocence or halo of motherhood and above all is white.

So, we aren’t shocked at the way the prominence of the term once again leaves in obscurity the deaths and abuse of so many other subjects that sovereignty does not recognize as worthy of grief. And grief is always the target, because grief sells.

The facts that are published and those concealed are very specific. Usually all the characteristics of the victim/survivor (name, age, origin, occupation, marital status) are exposed, contrary to those of the perpetrator. These characteristics, pass through a careful screening process, and so, only those focused on his relationship with the victim or that make him a tragic figure, who “broke” after an honourable life, are being published.

Those in charge (cops, judges, journalists) try to convince us that the hand of the woman-killer/abuser is armed by passion and love, and not by the deep-rooted patriarchy in the system and the feeling of ownership over our bodies.

Thus, the prevailing feeling in the audience is not one of rage for the abuser, but of sadness and of horror, for the victim. The emotions selectively evoked by the reproduction of information in the media, are those that are accessible to the consumer, but at the same time do not arouse reactions dangerous to the system. In the public sphere, the systemic origins of patriarchal violence in all its forms are ignored, resulting in the complete depoliticization of all incidents and the blunting of any social resistance that might arise.

Therefore, anger and rage, emotions which, when directed towards the oppressors, can be dangerous for them, are suppressed. After all, instead of the media functioning as an informative medium, they function as a propaganda tool of the ruling class.

The media is now itself a form of sovereignty and are rapidly shrinking into 5-6 giant companies. We are under no delusion that these were ever formed ‘bottom-up’, but the ridiculousness of this monopoly confirms that the real goal is not information (lol), but to overflow the pockets of the CEO technocrats.

The information that reaches the audience passes through the filters of the narrator- authority figure in each case. The media is turned into a tool for shaping public opinion, constructing perfect victims, based on the allies in power, and at the same time reproducing violence as a form of exemplification.

In other words, a one-way story is presented in order to be able to justify any violence resulting from the action – or inaction – of the dominant power. (see the representation of genocides in the US media).

At the beginning of the millennium, with the widespread use of the internet, new -decentralized- ways of transmitting information and exchanging ideas (blogs) were created. Media that were not initially recognized as potentially profitable.

Pop feminism

In 2010 in the US a pop/liberal feminism movement began, with a clear aesthetic based on a pink-purple background with bold lettering and titles of bad puns with the word [fem] as the first compound word. Its main purpose was to make feminism accessible, which established now widely known – and relatively unnecessary – terms such as mansplaining, manspreading etc. It ended up, however, being profitable for the – predominantly – wealthy, white female pioneers.

A non-radical idea of feminism is thus created. After all, what is profitable cannot be revolutionary. A movement that negates itself by focusing on the marketing of feminism rather than intersectionality. By evaluating and analyzing our common experiences simply as experiences, removing their political dimension and ignoring their systemic basis. Identifying the idea of feminism with the idea of the ‘biological woman’ as understood by sovereignty.

This form of feminism took shape through the online wave of #metoo. The me too movement, that differentiated from and premised on the online trend, was about empowering black survivors of sexual violence. The origins of this online wave can be traced to Alyssa Milano’s tweet in October 2017, where she pointed out that if all people subjected to abuse or harassment responded with the #metoo, it would immediately become a trend, which it did.

Social media flooded by posts with the hashtag, that very quickly gained momentum. Μany femininities shared their experiences, in a context of redemption, confession and even showing that harassment is a common experience in the daily life of a woman. Thus, #metoo was an opportunity to discuss experiences that were previously in a grey zone.

Immediately, masculinities who felt threatened reacted. Online arguments about what is defined as sexual harassment/abuse and what is not, took place (They themselves assigned very specific and targeted characteristics, those convenient for them, on how an experience is defined as rape). Survivors are questioned about the validity of their posts, and various stupid criteria are used to verify them, such as survivor status, age, origin, etc.

From time to time, various similar controversies or “dilemmas” appear on our home page, confirming and deepening the insecurity we as femininities feel towards men (we would choose the bear too).

The #metoo in Greece, started from an online interview of Sofia Bekatorou in January 2021, who spoke about her experiences in the field of sports. Thus, abusers were exposed, first from the field of sports, and then from that of theatre and cinema. Various celebrities gradually opened up and exposed their associates, triggering a wave of subsequent reports. Although #metoo was an opportunity to reveal the abusers, who for years were a big part of Greek entertainment, politically, #metoo functioned as firework activism and nothing more. (We also acknowledge that, at the time, quarantine, with the increase of domestic and gender violence, continual femicides and their non-stop display, contributed to the peak of this online activism).

The pop feminism movement is differentiated from previous feminist movements. While it achieved widespread reproduction, it remained inactive (political edging), thus fulfilling its self-imposed purpose.

In fact, pop feminism faded when it stopped being profitable. It collapsed completely when the internet was monopolized and concentrated on a few platforms: meta, twitter, tiktok, which very consciously discouraged the dissemination of links to external sites.

In former forms of media, the separation between transmitter and receiver was clear. The internet blurs the boundaries, and by reproducing the information consecutively, you become the transmitter as well (Take #metoo as an example). This creates the illusion of political action – but let’s not forget – no regime can fall from our couches.

Vast algorithms

The decentralisation of the internet has pushed the consumption of content, driven by vast algorithms. So our bodies, experiences and actions are computed and transformed endlessly into data streams.

We are ruled by social media platforms with clear political and financial interests. The product is us and by extension, our time. We are thus trapped in a continuous flow of information – interrupted only by advertisements. Our addiction to doom scrolling is the wet dream of every technocrat.

The fact that the algorithm is unbiased and at the same time personalized hides a “slight” dose of contradiction. Our online activity takes place in a bubble where we all agree with each other. The only thing that can – temporarily – pop it is the right-wing friendly “algorithm”. A bootlicking algorithm, since the ultimate goal of any company is to maintain the status quo. More to the point, even if we started from a hypothetical point 0, it wouldn’t take long for someone to go from innocent -in theory- videogame videos, to fascists, conspiracy theories and so on.

At the same time, sexists – supposed masters of flirting – almost monopolize and profit by exploiting the insecurities of young men – insecurities based on patriarchal ideals, while bottom-up political movements are shadowbanned and their speech never sees the light of day.

The aim of the platforms is the profit that results from long and continuous use. The most valuable user is the one who engages systematically with the content – but with no evaluation of whether their interaction is positive or negative. A cat video elicits no more than a smirk, as opposed to the dead bodies of children in Palestine, and the media knows this. Strong emotions- such as anger and sadness, which drive users to interact, are the most profitable [ragebait].

Contemporary, political activism is normalised and practised in the symbolic simulation of a public space – social media platforms, where collective action can be exclusively activated by evoking feelings of ‘solidarity’, ‘rage’ or ‘recognition’.

The Greek version of pop feminism was also created – after all, Greece is “just a fly on the shit that is US” [blind follower]: pink and purple backgrounds with bold lettering, provocative words and phrases, accompanied by emotionally charged images of women crying, tied hands, bruises etc., are here to let us know that we lost another sister.

We do not question the value of information, but let us not forget that movements that are born and remain on the screen are unable to take concrete action.

The media [old and new] try to distinguish themselves in cyberspace by appealing to our grief. We experience other emotions too, grief is real but grief pacifies. Anger is simply being channeled into the reproduction of information. A solution was finally found to venting without being dangerous; with a post or a comment. Without understanding that political action is something deeply collective, anger is expressed through personal/individual takes, ignoring the systemic root of the problem.

Since 2018 and after the femicide of Eleni Topaloudi, our systematic exposure to femicides has ultimately rendered us numb. Femicide is just another news story- so light that it is comfortably discussed on the morning shows, or between two cat videos.

For us, femicide is the quintessential of patriarchal violence. Patriarchal violence is deeply systemic. And deeply systemic problems are solved collectively and on the street.

Anarchoqueer feminist collective Tsoupres